My grandfather was a schoolteacher, a school principal, and a child psychologist. He was an advocate for the idea that children should memorize poems. I believe he thought it would improve language skills, help with understanding rhythm in speech, and show children the joy of becoming emotionally attached to words and stories. There were five grandchildren. I was the youngest. I didn’t really want to memorize a poem. I remember it was summertime, and it felt too much like schoolwork, but I did. I chose the poem “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” published in 1889 by Eugene Field. The original title of the poem was “Dutch Lullaby.” Field was known for his humorous newspaper columns and light verse for children. When I look back over my lifetime, I think my grandfather was onto something.

The poem is a charming, soothing rhyme about three children who go on a journey. They sail on a “river of crystal light” and “into a sea of dew.” They fish for stars and the moon sings to them, encouraging them as a friend and companion. Later, it becomes clear that the story is really about one child, his eyes are Wynken and Blynken, and his head is Nod. His mother is singing to him in his trundle bed of the, “…wonderful sights he’ll see.”

The poem was written at a time when people were fascinated with dreams. While it describes sleep, and falling asleep, and dreaming, it’s also about what you can do with your own imagination. It’s a lesson in fantasy. I have recited the poem in my head many times in my lifetime. I recited it to my children at bedtime. Like any good lullaby, it has comforted me and reminded me of hope, beauty, magic and that dreams can still come true. It is a piece of work that makes me feel safe. It has been my trusty companion. So perhaps it is true that all children should memorize at least one poem. I am not the only one who fell in love with “Wynken, Blynken and Nod” and stayed that way. Mankind in general has. It was made into a song in 1890 by Ethelbert Woodbridge. It was recorded as a song again in 1930 and later by the Doobie Brothers. The song was also performed on the television shows Barney & Friends and Sesame Street. In 1938, Walt Disney released an adorable cartoon on the poem featuring three pajama-wearing children. (You can watch this below.) In 1993, Mrs. Wilson recited the poem to Dennis in the movie Dennis the Menace. The poem is in the public domain and available to read from numerous sources, but here is the text:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod one night

Sailed off in a wooden shoe—

Sailed on a river of crystal light,

Into a sea of dew.

'Where are you going, and what do you wish?'

The old moon asked the three.

'We have come to fish for the herring-fish

That live in this beautiful sea;

Nets of silver and gold have we!'

Said Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

The old moon laughed and sang a song,

As they rocked in the wooden shoe,

And the wind that sped them all night long

Ruffled the waves of dew.

The little stars were the herring fish

That lived in the beautiful sea–

'Now cast your nets wherever you wish—

Never afeard are we';

So cried the stars to the fishermen three:

Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

All night long their nets they threw

To the stars in the twinkling foam—

Then down from the skies came the wooden shoe,

Bringing the fishermen home;

'Twas all so pretty a sail it seemed

As if it could not be,

And some folk thought ’twas a dream they’d dreamed

Of sailing that beautiful sea–

But I shall name you the fishermen three:

Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

Wynken and Blynken are two little eyes,

And Nod is a little head,

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

Is the wee one’s trundle-bed.

So shut your eyes while mother sings

Of wonderful sights that be,

And you shall see the beautiful things

As you rock in the misty sea,

Where the old shoe rocked the fishermen three:

Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

May you find it soothes you to sleep too!

Sweet dreams!

Virginia Watts is the author of poetry and stories found in The MacGuffin, Epiphany, CRAFT, The Florida Review, Reed Magazine, Pithead Chapel, Eclectica Magazine among others. She has been nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize. Her debut short story collection Echoes from the Hocker House was short listed for 2024 Eric Hoffer Grand Prize, selected as one of the Best Indie Books of 2023 by Kirkus Book Reviews, and won third place in the 2024 Feathered Quill Book Awards. Please visit her.

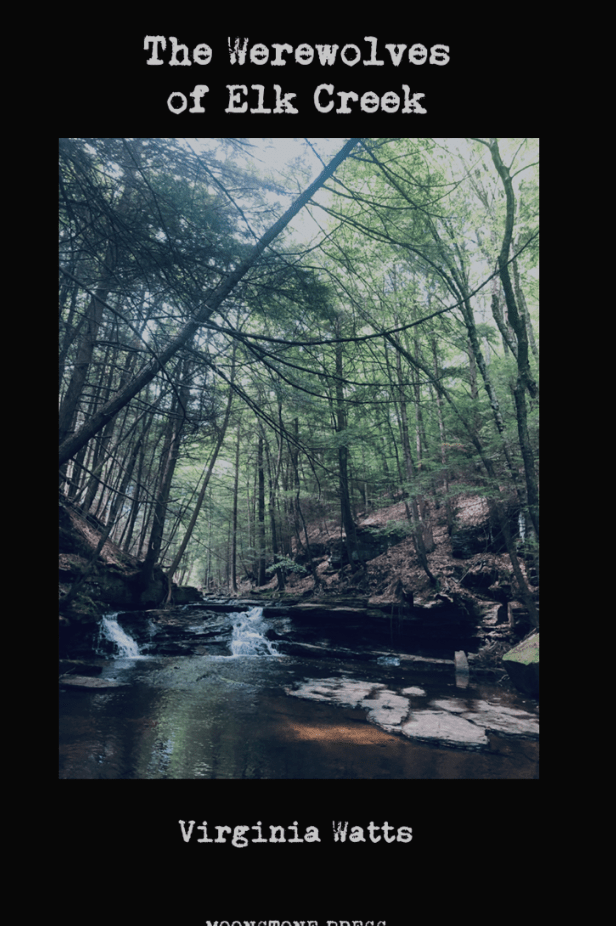

Virginia’s new book is now available from Old Scratch Press:

Her prior poetry chapbooks Shot Full of Holes and The Werewolves of Elk Creek

are available from Moonstone Press. And her debut short story collection Echoes from the Hocker House is not to be missed!